The Great Hunger

The Irish Potato Famine (also known as “The Great Hunger” to designate a root cause of food distribution, rather than scarcity) occurred between 1845 and 1849. Though triggered by a potato blight which destroyed most potato crops throughout Europe in the 1840s, the blight itself was not enough to cause the widespread famine that followed in Ireland. Many factors led to The Great Hunger, including widespread poverty brought on by tenant farming in Ireland; potatoes serving as the only source of food for most Irish people; and a lack of aid from England, which ruled over Ireland at the time. These conditions created a famine which devastated Ireland, causing around one million deaths from starvation or famine-related diseases and resulting in the emigration of another one to two million Irish people, most of whom fled to America.

The Irish Potato Famine (also known as “The Great Hunger” to designate a root cause of food distribution, rather than scarcity) occurred between 1845 and 1849. Though triggered by a potato blight which destroyed most potato crops throughout Europe in the 1840s, the blight itself was not enough to cause the widespread famine that followed in Ireland. Many factors led to The Great Hunger, including widespread poverty brought on by tenant farming in Ireland; potatoes serving as the only source of food for most Irish people; and a lack of aid from England, which ruled over Ireland at the time. These conditions created a famine which devastated Ireland, causing around one million deaths from starvation or famine-related diseases and resulting in the emigration of another one to two million Irish people, most of whom fled to America.

Even before the famine, the people of Ireland lived in extreme poverty. During this time, Britain ruled over Ireland. Almost all land in Ireland was owned by Protestants of British and Anglo-Irish descent. These landowners often leased their lands to “middlemen” who paid a fixed rent in exchange for managing the lands, hiring farmers, and collecting the rent from farmers. As a result, the middlemen tried to extract as much money as possible from the land and tenant farmers. These middlemen often used a tactic of splitting up the land they managed into plots as small as possible, in order to squeeze in more families to collect rent from . These small plots of land paired with high rents forced the farmers to plant potatoes almost exclusively, as it was the only crop that could grow enough food to feed their families. The middlemen could also evict tenant families at-will for missing a payment or by deciding the land should be used to farm something else. Once evicted, any tenant improvements to the land (like building houses and other kinds of shelter) became property of the landowner. As a result, tenants rarely built housing, and families often had only shacks to live in.

Britain’s response to the blight was not nearly enough to prevent the resulting famine. The lack of response was due, largely, to apathy caused by anti-Catholicism in Britain. England’s Protestant elite believed the blight was sent by God to punish the Irish, who were almost entirely Catholic. In light of this popular sentiment, Britain sent little food or money to help Ireland. The famine became far worse than it would have, had Britain responded appropriately. Irish activist John Mitchel wrote in 1860:

I have called it an artificial famine: that is to say, it was a famine which desolated a rich and fertile island that produced every year abundance and superabundance to sustain all her people and many more. The English, indeed, call the famine a ‘dispensation of Providence’ and ascribe it entirely to the blight on potatoes. But potatoes failed in like manner all over Europe; yet there was no famine save in Ireland. The British account of the matter, then, is first, a fraud; second, a blasphemy. The Almighty, indeed, sent the potato blight, but the English created the famine.

The Mexican-American War

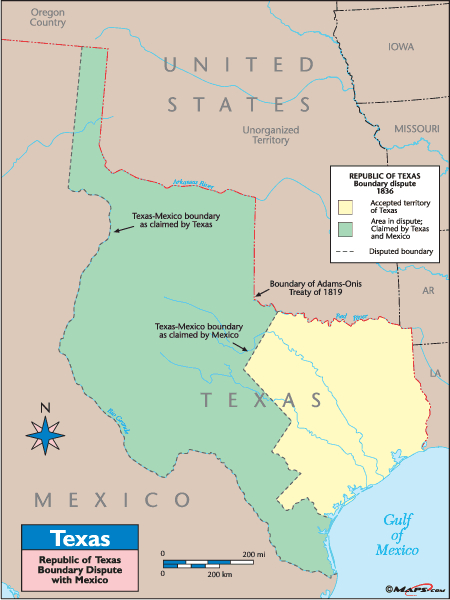

The Mexican-American War (1846-1848) transpired directly after the United States’ annexation of the Republic of Texas, which had revolted and declared itself independent in 1836. After the Texas Revolution, Mexico refused to recognize Texas as an independent republic and claimed the land was still part of Mexico. The Texas-Mexico border was heavily disputed, with Mexico claiming the border was drawn by the Nueces River and Texas claiming the border was drawn by the Rio Grande. Texas’ claim came from the Treaties of Velasco (signed by General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna), which designated the Rio Grande as Texas’ border. However, General Santa Anna was coerced into signing the documents as a prisoner of war, and Mexico never ratified the treaties.

After the U.S. annexed Texas, President James K. Polk began preparation for a war with Mexico. He sent General Zachary Taylor to occupy the disputed region between the Nueces and Rio Grande in the hope that Mexico would retaliate, starting a war in which the U.S. could take more of Mexico than just Texas. President Polk’s deliberate provocation came from a prevailing belief that the U.S. was destined to expand across North America (see Manifest Destiny). The resulting war was described in the Republican Campaign Textbook (1880) as “one of the darkest scenes in our history—a war forced upon our and the Mexican people by the high-handed usurpations of Pres’t Polk in pursuit of territorial aggrandizement of the slave oligarchy.”

El Batallón de los San Patricios (The Battalion of the Saint Patricks)

John Riley, the commander of the San Patricios, was a native of Galway. He was a veteran of the British Army and immigrated to Mackinaw Island in 1843. A skilled and experienced artillerist, he enlisted in the U.S. Army on September 4, 1845. The U.S. Army experienced many desertions, particularly among foreign nationals. Many Americans were anti-immigration, anti-Catholic, and generally xenophobic. Known as the “Know Nothing Party,” some believed that Roman Catholics were conspiring to subvert civil and religious liberty in the States. Many with these views were officers in the U.S. Army and inflicted harsh and unfair punishment to the Catholic immigrants under their command. The U.S. Army was also a Protestant Army; there were no Catholic chaplains or Mass for foreign nationals to attend.

On April 12, 1846, John Riley secured a pass to attend Mass outside of General Taylor’s camp. He made his way to the Rio Grande, swam across, and was captured by Mexican soldiers who took him before General Pedro de Ampudia. Impressed with Riley, Ampudia offered him a commission as a first lieutenant in the Mexican Army.

Riley and a company of 48 Irishmen served as artillery crews in the Siege of Fort Texas. At the same time, the Legión de Extranjeros (Legion of Foreigners), comprised mostly of immigrants who later made up the core of Los San Patricios, fought in the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma.

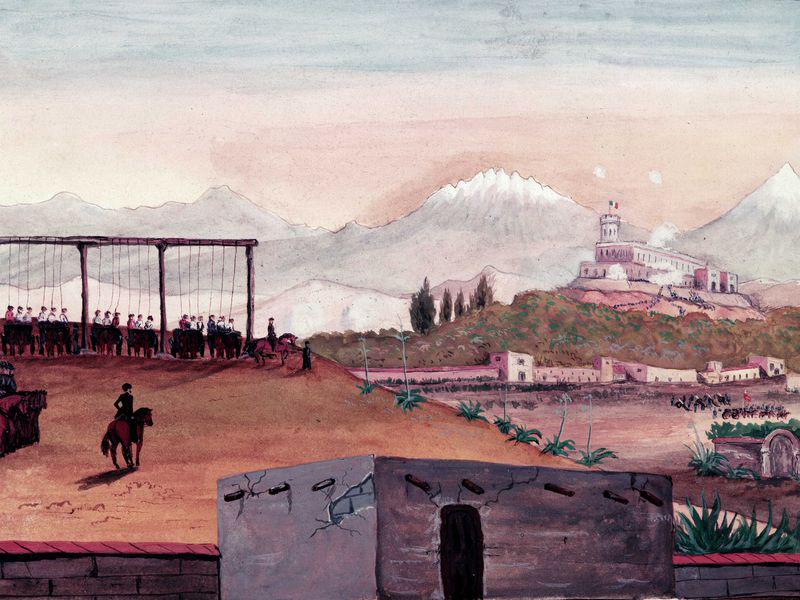

Los San Patricios first fought as an official Mexican unit in the Battle of Monterrey under the leadership of John Riley (September 19–24, 1846). After this engagement, the San Patricios grew in size with estimates of enlistment ranging from 200 to 700 men. They went on to fight in the Battle of Buena Vista (February 24, 1847), the Battle of Cerro Gordo (April 17–18, 1847), and the Battle of Churubusco (August 20, 1847). In their last battle, the San Patricios and the rest of the Mexican troops were completely outnumbered. The Mexicans fought until they ran out of ammunition, at which point a Mexican officer raised the white flag of surrender. Officer Patrick Dalton of the San Patricios tore the white flag down, prompting General Pedro Anaya to command his men to fight with their hands if they had to. The Mexicans tried to surrender two more times and were shot and killed by members of the San Patricios, who refused to surrender. A total of 35 San Patricios were killed and 85 were taken prisoner (including John Riley). Those that escaped regrouped and went on to fight at the Battle of Mexico City.

Those captured were handled as traitors, as they were responsible for some of the greatest casualties the U.S. Army had faced. 72 of the captured were immediately charged with desertion and sentenced to hang. This sentence violated the Articles of War, which required death by firing squad as the penalty in time of war. Hanging was reserved for spies and those who committed “atrocities against civilians,” neither of which the San Patricios were charged with.

The soldiers who deserted before the war started (including John Riley) were sentenced to “receive 50 lashes on their bare backs, to be branded with the letter ‘D’ for deserter, and to wear iron yokes around their necks for the duration of the war.”

Riley was a prisoner of the U.S. until the end of the war. He served in the Mexican Army until he was involved in an aborted coup attempt. Riley’s life after this is unknown. Legend has him living out his days in the mountains of Mexico, with some saying he returned to his native Ireland.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The United States captured Mexico City at the end of 1847. On February 2, 1848, Mexico and the U.S. signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. In exchange for 15 million dollars (about five cents per acre), the treaty called for Mexico to cede the land of what is now California, Nevada, Utah, most of Arizona, half of New Mexico, and parts of Colorado and Wyoming, totaling 529 thousand square miles of land. The treaty also ensured the property rights of Mexican citizens who owned land in these territories. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, the U.S. did little to actually enforce the existing property rights of Mexicans as Americans settled in those lands in the subsequent years.) The treaty also offered U.S. citizenship to all Mexican residents of the ceded land.

Further Reading:

Irish Potato Famine

Gallagher, Thomas. Paddy’s Lament, Ireland 1846–1847: Prelude to Hatred. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1987.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/famine_01.shtml

https://www.britannica.com/event/Great-Famine-Irish-history

Anti-Catholicism in the U.S.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-Catholicism_in_the_United_States

The San Patricios Battalion

http://chicago.indymedia.org/archive/newswire/display/73967/index.php

https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2013/03/the-san-patricios-the-irish-heroes-of-mexico/

The Texas Revolution

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Texas-Revolution

The Mexican-American War

https://www.britannica.com/event/Mexican-American-War

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/guadalupe-hidalgo